Mark Campbell and the Ethics of Saying Less

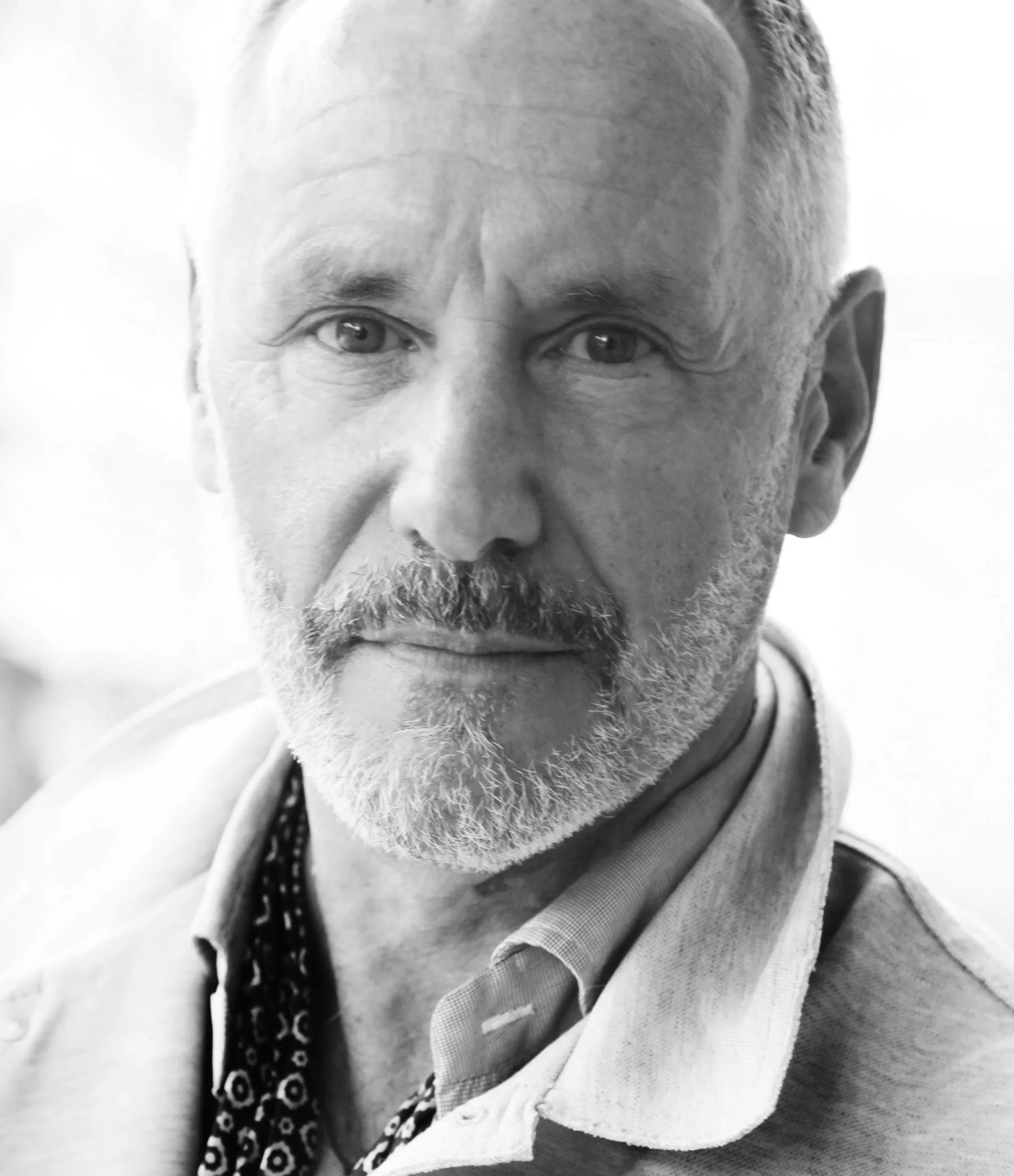

Mark Campbell - Librettist

On Libretto, Silence, and the Work of a Pulitzer- and GRAMMY-Winning Librettist

The Moral Weight of the First Sentence

Opera does not begin with music.

It begins with permission.

Permission for sound to exist, for breath to matter, for silence to carry meaning. Before a composer can imagine harmony or rhythm, the libretto must answer a more difficult question: why must this be sung? For Mark Campbell, one of the most consequential librettists in contemporary American opera, this question is not aesthetic; it is ethical.

Campbell’s work is defined not by linguistic excess, but by restraint. In an art form often associated with grandeur and overflow, he has built a career on clarity, discipline, and the radical choice to say less. His librettos do not ask language to dominate the stage. They ask it to step aside at the right moment, trusting music to complete the thought.

This philosophy, libretto as moral architecture rather than verbal display, has reshaped the contemporary operatic canon and redefined what it means to write words worthy of music.

From Performance to Construction: Choosing the Right Kind of Voice

Campbell’s artistic life began in the theater, trained as an actor and drawn to the immediacy of performance. But early on, he encountered a realization that would quietly redirect his future: acting was not where his deepest strength lived. Rather than clinging to visibility, he followed a subtler instinct toward authorship.

When asked to write lyrics for musical theater, Campbell discovered a different kind of presence. Writing allowed him to shape intention, timing, and emotional trajectory without occupying the spotlight. He found freedom in construction rather than performance, in designing the conditions under which others could speak, sing, and inhabit character.

A lifelong admirer of Stephen Sondheim, Campbell absorbed a core lesson that would stay with him: language in musical drama is functional before it is decorative. Words exist to move time forward, to clarify stakes, and to create momentum. Anything else is indulgence.

Discovering Opera: Freedom Through Submission

In 2000, Campbell was invited to write his first opera. By 2004, he had fallen decisively in love with the form.

What drew him in was not spectacle, but hierarchy. Opera, he realized, places music above language, and demands that the librettist accept that order fully. For someone who loves music deeply, this was not a loss of power but a moral alignment. In opera, the libretto does not compete with sound; it earns it.

This distinction separated opera from musical theater in a way that mattered profoundly to Campbell. Opera, he felt, honored the composer more honestly. It required the librettist to relinquish control, to trust that music would do the deeper emotional work. This act of submission, rare in any art form became central to his practice.

Against Ornament: Clarity as Responsibility

Mark Campbell’s approach to language is not defined by avoidance, but by choice. He writes with intention, guided by a clear belief that the libretto exists to create space for music, not to compete with it. For Campbell, lyricism is not measured by ornament or density, but by function, by whether language advances drama and allows sound to speak.

He does not seek metaphor for its own sake, nor does he treat poetry as a display of verbal skill. Language that calls attention to itself risks interrupting music’s emotional work. In Campbell’s view, restraint is not minimalism; it is responsibility. A clear libretto gives music the freedom to carry ambiguity, contradiction, and depth without obstruction.

Two questions remain central to his process:

Why should the audience care?

Why does this story need to be told through music?

If the second question cannot be answered with honesty and necessity, Campbell believes opera is not the right form. Music, in his practice, is never incidental. It is too powerful and too consequential to be used without purpose.

Libretto and Score: Shared Authority, Shared Risk

One of the most persistent myths surrounding opera is that composers write first and librettists arrive later to “add” text. Campbell has spent much of his career dismantling this misconception. Libretto and score, he insists, are born together, in dialogue, negotiation, and trust.

This belief has made him a vocal advocate for equal recognition of librettists alongside composers. Opera is not a hierarchy of authorship; it is a shared act of creation. To deny that is to misunderstand the form entirely.

In collaboration, Campbell prioritizes time, time spent listening to a composer’s music, absorbing their instincts, and understanding how they think in sound. Mutual respect allows disagreement without rupture. When a composer diverges from the text, Campbell can articulate his original intention without defensiveness because the relationship is grounded in trust.

Writing in Time: Rhythm, Silence, and Listening

Rhythm, for Campbell, is not merely musical, it is dramatic. His librettos are shaped by an acute awareness of time as lived experience rather than measurement. He writes for the pause before a confession, the silence that follows a laugh, the suspended breath after a devastating truth. These moments are not ornamental; they are where meaning settles. In Campbell’s work, time is not filled, it is allowed.

This sensitivity to timing reflects a deep respect for the body and for listening. Language, in his view, must move at the speed of human response. A line that arrives too quickly denies the audience the chance to feel; a silence held too long risks becoming self-conscious. Writing, therefore, becomes an act of calibration, of sensing when to advance and when to wait.

Revision is central to this process, and revision, for Campbell, begins with listening. Especially in rehearsal, music reveals truths that language alone cannot predict. What reads clearly on the page may falter in sound; what seems spare in text may bloom once sung. Campbell listens closely to what the music teaches him, allowing sound to reshape language without surrendering dramatic intent.

Although his librettos are carefully structured, Campbell does not treat structure as fixed. He remains constantly available, on call to adjust, refine, and respond as the work takes shape. Structure, in his practice, is not rigidity but readiness: a framework designed to withstand change without losing coherence.

When differences arise in collaboration, Campbell returns to a grounding principle: everyone involved wants the work to be its best. This shared commitment reframes disagreement not as conflict, but as care. Through listening, patience, and mutual respect, friction becomes focus, and revision becomes clarity.

Building a Living Canon

The scope of Campbell’s contribution to American opera is extraordinary. His Pulitzer Prize–winning Silent Night and the widely produced As One have become pillars of the contemporary repertoire. The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, which received a GRAMMY Award for Best Opera Recording, demonstrated that modern stories, technological, ethical, and intimate, belong fully on the operatic stage.

Across more than forty opera librettos, numerous musicals, song cycles, and oratorios, Campbell has consistently chosen stories audiences recognize and care about. His works endure not because they are fashionable, but because they are necessary.

Advocacy Beyond the Page

Campbell’s influence extends far beyond his own writing. He is a tireless advocate for contemporary American opera and for the writers who shape it. Through mentorship roles with American Opera Projects, American Lyric Theatre, and Washington National Opera’s American Opera Initiative, he has helped guide future generations of librettists.

In 2020, he created and personally funds the Campbell Opera Librettist Prize, the first and only award dedicated exclusively to opera librettists. In 2022, he helped establish the True Voice Award, supporting the training of transgender opera singers. These initiatives reflect a belief that opera must not only evolve aesthetically, but ethically.

Saying Less, So Music Can Speak

Campbell’s advice to young librettists is deceptively simple: music is more powerful than words. The task of the librettist is not to compete with sound, but to prepare the space in which sound can speak fully.

This is the ethics of saying less.

Not absence, but intention.

Not silence, but trust.

In an art form defined by collaboration, Mark Campbell has mastered one of opera’s rarest disciplines: knowing when language must lead, and when it must step aside. His work reminds us that opera begins not with sound, but with responsibility.

And that sometimes, the most powerful thing a writer can do is make room.